Twice wiped out by hurricanes, Indianola lives on in the romance of Texas history

Michael Barnes

Michael Barnes

INDIANOLA, Texas — The romance of Indianola is hard to resist.

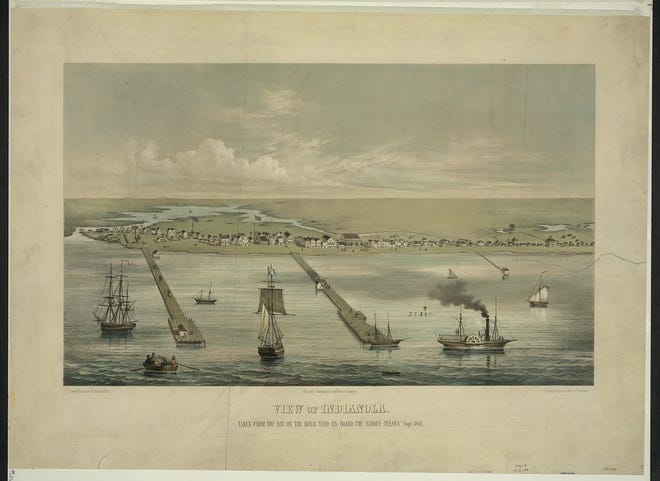

Twice wiped off the face of the Earth by hurricanes, it was once the second-largest port on the Texas coast, after Galveston. For decades, it ranked as one of the biggest cities in the state.

Thousands of immigrants, many of them from Germany, entered Texas through Indianola, located on a spit of sand along the western shore of Matagorda Bay. Via oxcart trails and, later, the "Old Salty" railroad, it became the gateway to the interior of Texas and Mexico.

Indianola has inspired novels such as Elizabeth Crook's "The Madstone" and Myra McIlvain's "Stein House," as well as focused histories, including Brownson Malsch's definitive "Indianola: The Mother of West Texas" and Curtis Foester Jr.'s short, charming memoir, "Camp Indianola and Other Stories, 1939-1950."

Don't look now:Austin and San Antonio are more alike than you think. Here's how.

This cosmopolitan city — which once hosted a commodious theater, hotels and restaurants — is no more. Much of it lies submerged in Matagorda Bay, to the delight of treasure hunters. Some buildings were rescued after the hurricanes of 1875 and 1886 and moved inland.

Today, a thin string of holiday cabins hiked up on stilts lines the connected communities of Indianola, Indian Point (Old Indianola) and Magnolia Beach.

Published sources often call it a ghost town.

Soft-spoken history expert Gary Ralston, who showed me around historic Port Lavaca, which I described in last week's column, was my guide to Indianola, too. Today, I can merely skim the surface of its history, but I promise to return to the subject in the future.

When the Karankawa ruled the coast

For centuries, the lower Gulf Coast of Texas belonged to the Karankawa. They were the first Native Texans encountered by the Spanish when Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and his shipmates washed ashore farther up the coast in 1528.

Described as tall and striking, the Karankawa migrated seasonally across the coastal plain to take advantage of oysters, pecans and other sources of sustenance and reportedly used alligator fat to ward off mosquitoes.

'We're home':140 years after forced exile, the Tonkawa reclaim a sacred part of Texas

When American colonists arrived in numbers during the 1820s, Stephen F. Austin and other leaders sought to exterminate the Karankawa. And many Texas history books have counted them as extinct.

Recently, however, more than 100 Karankawa Kadla have connected on social media. Not recognized by federal or state authorities, they have shared their histories with reporters and scholars. They also have protested industrial developments on ancestral lands.

"Some families are certain they are Karankawa and say their history and culture have been diligently passed down from generation to generation," reports Erin Douglas in the Texas Tribune. "But most have to piece together their heritage from family oral history, DNA tests and what little documentation exists in historical archives, such as those from Spanish missions."

The Spanish versus the French

Explorer and mapmaker Alonso Álvarez de Pineda glided up the Texas coast in 1519 looking for — what else? — a passage to Asia. After that, the Spanish left the Matagorda Bay area alone for a while.

Not the Alamo:Fields near San Antonio yield evidence of deadliest battle in Texas history

The Spanish took notice, however, when French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, sailed into Matagorda Bay in 1685 to plant a colony in what he thought was part of Louisiana. In the past, some historians suggested that La Salle, who was killed by his own men in East Texas, and whose colony was destroyed by the Karankawa, had originally set up his stockades not far from Indianola. In fact, archeological remains were found on Garcitas Creek, which feeds into Lavaca Bay, an arm of Matagorda Bay.

Nevertheless, La Salle is the subject one of the grandest monuments in Texas. It rises at the terminus of Highway 316 between Indian Point and Indianola. Created by sculptor Raoul Josset and architect Donald S. Nelson for the Texas Centennial, and dedicated in 1939, the angled, art-deco masterpiece shows a caped La Salle, sword in hand, gazing into the bay as if facing steady winds.

At age 9, I first visited this statue, which I still find among the most inspiring in the state, even though the more I learn about La Salle, the person, the less he seems worthy of such glorification.

For their part, the Spanish sent several expeditions to find La Salle's colony, which the Karankawa had destroyed. They also redeemed the French children who had been taken captive, and they planted a presidio and mission on the spot.

"The Presidio La Bahia and its mission were first established on Garcitas Creek in 1721," Ralston says. "It was next moved to the Guadalupe River in Victoria County and then finally to the San Antonio River near Goliad. The presidio was also built over the location of La Salle’s ‘fort’."

Recently, another historical marker went up next to the La Salle monument. It honors Louis Antoine Andry, a.k.a Luis Antonio Andry, an 18th-century French engineer whom Louisiana governor Bernardo de Gálvez drafted to map the Gulf of Mexico coast from the Mississippi River to Matagorda Bay. He and his crew ended up crosswise with the Karankawa, but his descendants have done excellent work in reviving his story. I'll return to that subject in a later column.

The first Germans arrive

Prince Karl of Solms-Braunfels, namesake of New Braunfels, is credited with establishing the landing that became Indianola in 1844. Two years earlier in Germany, a humanitarian group known as the Adelsverein vowed to buy land in Texas and support settlers escaping political upheaval in Europe. It acquired large tracts on the Comal River at New Braunfels and, farther out in the wilderness, in Fredericksburg.

More:Tracking Germans in Texas with James Kearney

The port on the shell beach at Indian Point was first known as Karlshafen and later as Indianola. The settlers' introduction to Texas wasn't easy. There was little shelter for the newcomers, and only those with money could obtain oxcarts. Many died.

One reason for the many arrivals in this shallow bay instead of, say, Galveston: The region upstream is not obstructed by major Texas rivers such as the Colorado, Brazos or Trinity, which are nearly impossible to cross at flood levels.

Gateway to the West

Ports generate fresh activity deep inland. Indianola was no exception. Early on, its trails west led all the way to Chihuahua City, Chihuahua. Silver, copper, zinc and lead from the Chihuahuan mines headed to eastern markets through Indianola on what was sometimes called the Goliad Cart Road, an alternative to the longer Santa Fe Trail. Scores of settlements were put down in West Texas along that road during the 30 years of Indianola's prominence.

Meanwhile, Germans, Czechs, Poles and Americans scattered over the region. It is safe to say that from 1844 to 1886, most immigrant communities established below the Colorado River and above the San Antonio arrived through Indianola.

Texas History:Peer into the daily lives of early German Texans

The days of freighters and oxcarts making their arduous way across Texas and Mexico from Indianola ended in 1860 when the San Antonio and Mexican Gulf Railroad and the Indianola Railroad joined up in Victoria.

Two big storms end a city's life

To many Texans, Indianola's story begins and ends with the big hurricanes of Sept. 17, 1875, and Aug. 4, 1886. The first almost completely destroyed the city, and the second, along with a fire, finished the job.

Descriptions of the storms are as harrowing as those regarding the more famous 1900 hurricane that hit Galveston, the deadliest natural disaster in American history. One reason might be that nobody has written a modern account of Indianola's disasters as popular and enduring as Erik Larson's history of the one that struck Galveston, "Isaac's Storm: A Man, a Time, and the Deadliest Hurricane in History."

Texas History:Among Galveston's historical gems, don't skip the Rosenberg Library

Ralston and I visited two evocative Indianola graveyards, one at Indian Point, called the Old Town Cemetery, is located on an elevated ridge within what is now a bird sanctuary. Angelina Eberly, the hero of the Archives War in Austin — there is a statue of her on Congress Avenue — and an innkeeper at San Felipe de Austin, is buried here. She died in 1860.

The larger Indianola Cemetery is guarded by a statue of La Salle, cut off at the knees by time. In some ways, it is more to the point than the glorious La Salle monument down the road.

Indianola at war

When defending a port, one must keep an eye out for enemy armies and navies.

During the 1830s, what later became Indianola did not figure into the major battles of the Texas Revolution, although some troops likely moved through what would become Calhoun County.

During the 1840s, nearby Lavaca was active in landing supplies and soldiers that moved inland for the Mexican War efforts.

During the 1850s, western Texas was situated on the front lines of the U.S. wars against the Native Americans, and Indianola played key a role, as a port of entry not only for federal soldiers, but also for immigrants headed into that territory, which further aggravated hostilities.

Texas History:Forts evoke a rough and isolated, but well-ordered, frontier life

One interlude during this decade has delighted schoolchildren ever since.

"No immigrants arriving in Indianola were as exotic as the 75 camels that came ashore in in 1856 and 1857 from Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt and Turkey," reads the Texas Historical Marker at the terminus of Highway 316 on Matagorda Bay.

It must have been like the circus coming to town. Whole books have been written about the attempt by the U.S. Cavalry to transplant Bactrian, Arabian and hybrid camels to Texas. Later stationed in places such as Camp Verde, Texas, the camels helped survey desert roads to California. During the Civil War, they became Confederate property; after the war they were auctioned off.

On a sillier note, the imported camels became the subject of a 1976 slapstick Western movie, "Hawmps!"

During the 1860s, Matagorda Bay was under Union blockade. Before naval fireworks began, federal troops who had been stationed at forts to the west gathered in Indianola to be evacuated.

During the 1930s and '40s, what was left of Indianola was turned into a major training base for thousands of artillerymen.

In his memoir, Curtis Foester Jr. writes of how he and his ranching family — which by luck owned an airplane — interacted with the soldiers bivouacked at Camp Indianola. Some of his memories are of everyday things such as the soldiers' loneliness, but Foester also dramatizes major events, such as the evacuation of the military in the face of yet another hurricane. Soldiers assigned to the higher ground around his family's ranch at first said they would be fine camping nearby in tents, but eventually battened down the hatches at the ranch house.

Today, one can easily spot the concrete foundations of the long-gone barracks.

Indianola today

On a sunny day in late February of this year, Indianola looked like any other vacation spot on the Texas coast. Snowbirds — tourists from the North — circled in RV camps. An old-school outfit, Indianola Fishing Marina, Bait Shop and Restaurant, built out over Powderhorn Bayou, brought out one set of visitors. A dedicated birding sanctuary attracted another. Casual bicyclists looped around the one main road.

One historical marker on Powderhorn Bayou honors David Edward "Ed" Bell, a virtuoso storyteller who was born near Leakey in 1905 and for decades operated Ed Bell's Fish Camp with wife Mary Alma Smith Bell.

Who has not heard the best of Texas tall tales as told in a bait shop or feed store?

One thing that visitors here cannot escape is history. There is a monument, cemetery, interpretative sign or historical marker planted every few yards.

A certain sadness hangs over this place, where many, many people died in the terrible winds and storm surges, or were pushed out by newcomers from overseas, or were stricken by disease and assailed by the elements while waiting to trek inland.

Yet Indianola was a place. An important place. And while no longer a city like its onetime rival, Galveston, it has not slipped into oblivion.

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@gannett.com. Sign up for the free weekly digital newsletter, Think, Texas, at statesman.com/newsletters, or at the newsletter page of your local USA Today Network paper.